Scales of Sharing

Communal living beyond the household

Throughout California history, precarity and idealism have brought forth radical forms of sharing. The resulting experiments in sharing tools, knowledge, domestic environments, labor, resources, and governance have gained new relevance today when the impacts of climate change and the pandemic are challenging us to think about community and at a scale larger than ourselves. Yet, it is precisely the acts of commoning in our most intimate environment —domestic space— that can teach us how to inhabit our cities in ways that are more communal and sustainable. It entails reseeing the city as a “commons,” and engaging in commoning as a social act in which we cultivate relationships with others for the collective care of the resources we share.

As one experiment in commoning, the communes in the 1960s dominate narratives of the West Coast, and California in particular. Part of the back-to-the-land movement, a majority of the communes founded at that time situated themselves in the urban hinterland. Often described as an act of withdrawal from the city, society and government, it was in equal measure the desire for “world-building” that drove the communards to rural areas. The relative isolation of the hinterland communes highlighted the need for, and benefits of, joint management of everything from childcare to—often scarce—funding, food, and energy resources.

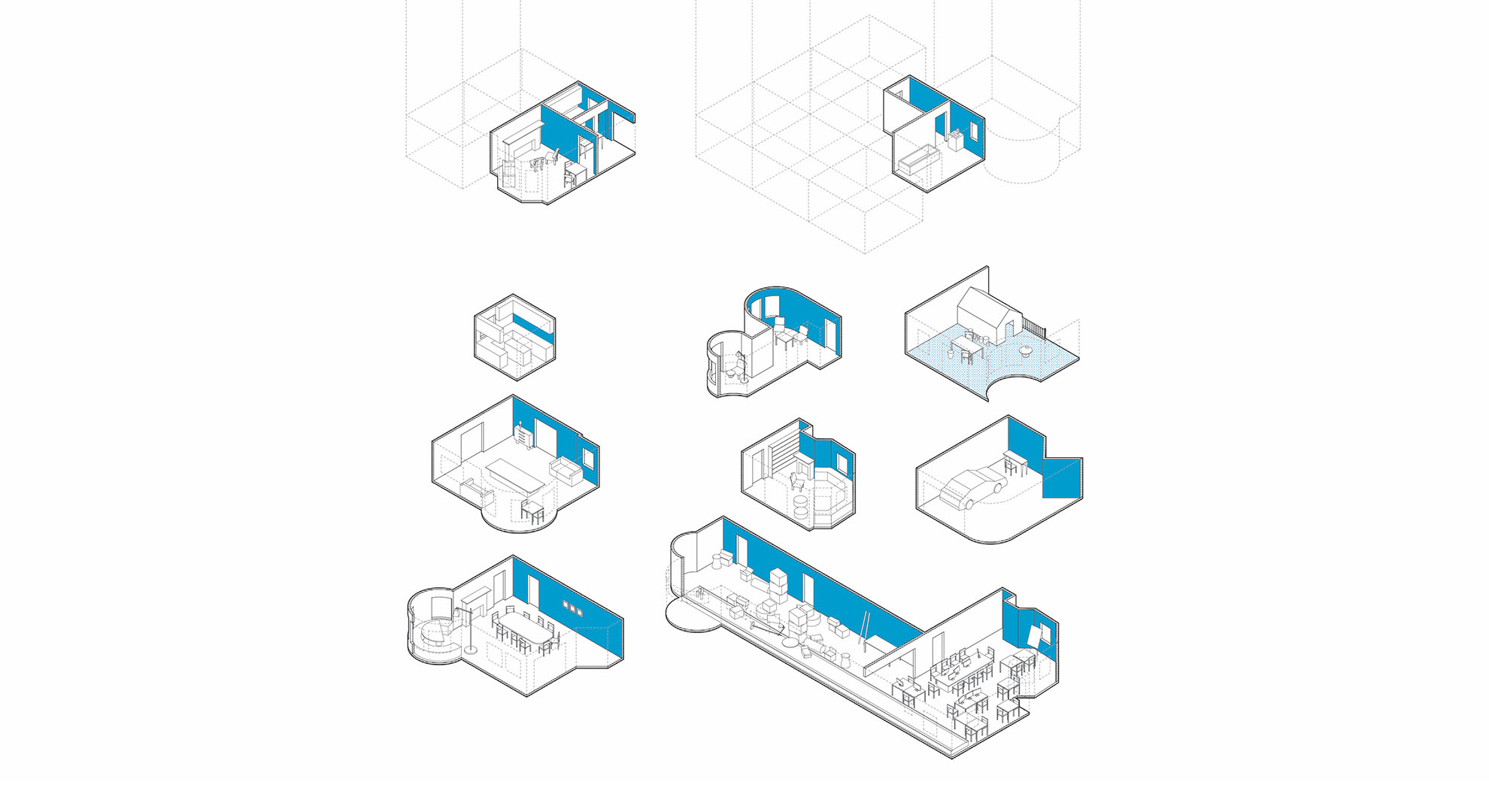

Our research into the resurgence of communal living reveals that sharing is more nuanced in today’s urban intentional communities. Examining what is being shared, and by whom, reveals multiple tiers of access to resources that we refer to as scales of sharing. Only a handful of people might share a bathroom while twelve share a kitchen and everyone in the house jointly uses its living spaces. The sharing of bed or bathrooms builds increased familiarity with some community members and allows maintenance of these spaces to be more easily managed.

Sharing domestic space at different scales, Embassy Commune, San Francisco. Image © Antje Steinmuller and Neeraj Bhatia

At San Francisco’s Embassy commune, amenities shared by all include multiple living spaces in addition to a greenhouse, outdoor shower, a bowling alley, and sauna. The fact that multiples of spaces exist in proximity facilitates negotiations over their use and accommodates experimentation over time. One of the Embassy’s living rooms became the “Anti-Social Social Room,” a space where residents could gather with others, yet be left alone. The adjacent living space hosts regular discussions on community governance, another aspect of living communally that requires frequent assessment and negotiation, and remains in a constant state of becoming. Privacy, within this multilayered shared environment, is not tied to the bedroom, but rather occupies nooks and crannies—the small greenhouse, the sauna, or a chair in the Anti-Social Social Room.

Experiments in world-building continue today. Ephemerisle, a weeklong gathering in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, builds a temporary social space that understands itself as testing ground for a future in which humans are forced to migrate into the ocean. Each summer, self-built floating structures connect with boats into a small city on water that experiments with nonhierarchical forms of governance informed, for some, by libertarian ideals. Operating by word-of-mouth and without tickets or fees, resources are shared among a changing group of participants, some of whom come to party while others partake for the social experiment of collective survival on water.

Ephemerisle’s founder, Patri Friedman, executive director of The Seasteading Institute, has emphasized incrementalism as part of building new societies. An incremental process of learning from experimentation —favoring organic evolution over top-down change— also appears to characterize many sustainable intentional communities who share a household. As we consider how lessons from shared domestic space might scale up to inform the contemporary city, imagining incremental processes might prove equally necessary. It begins with interrogating our notions of, and need for privacy, finding it perhaps in urban spaces.

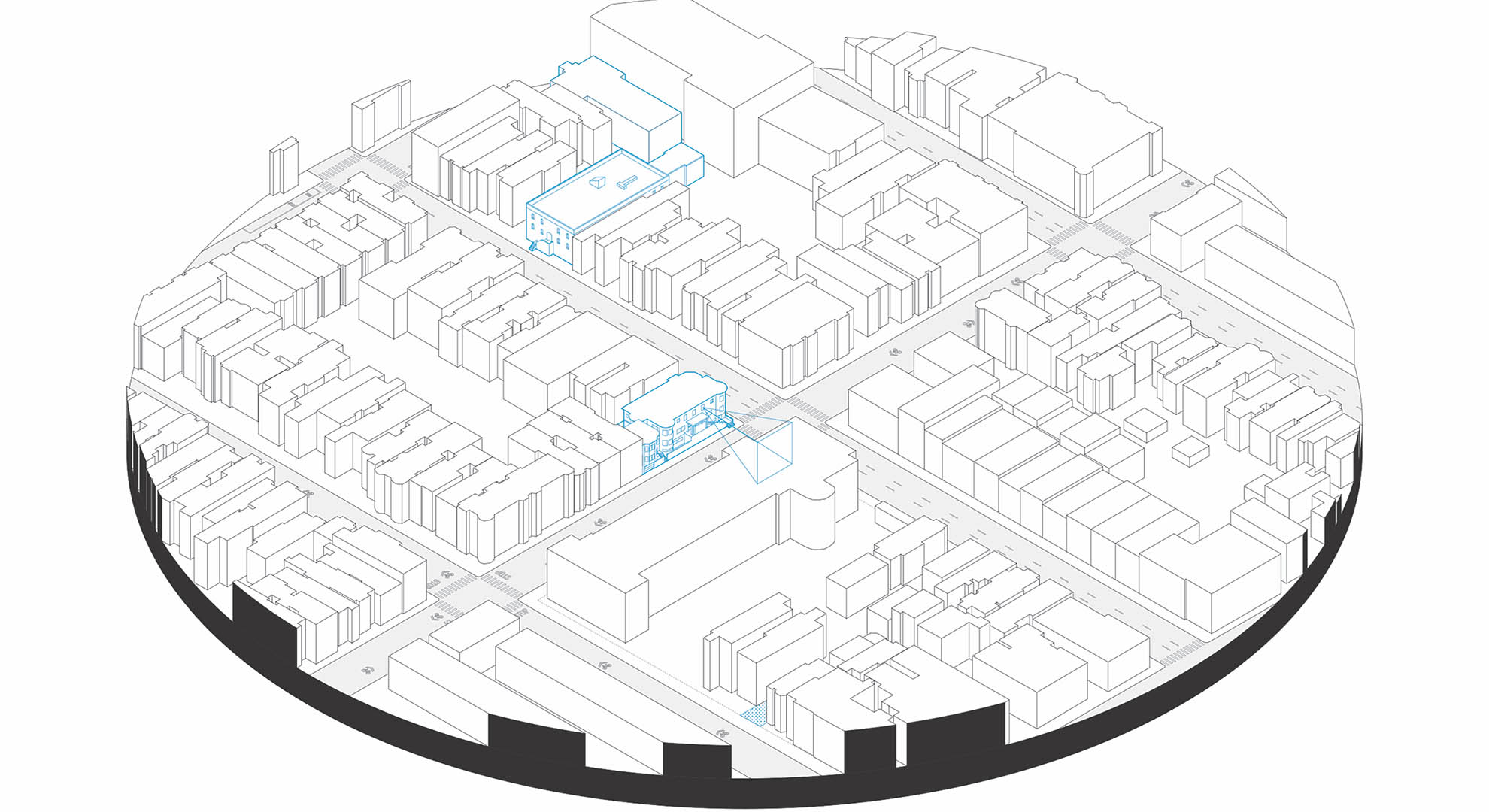

Networked sharing beyond the household in the neighborhood, Embassy Commune, San Francisco. Image © Antje Steinmuller and Neeraj Bhatia

Learning from “domestic commoning” in places like the Embassy commune for the remaking of cities requires the legal redefinition of what constitutes a family. As the nuclear family occupies only about 30% of households, we might need to collectively reenvision how we build housing that better accommodates the desire for different kinds of social units, and the scales at which communities of individuals share space. As scales of sharing expand to the neighborhood as a commons, the form of urban spaces needs to prioritize accessibility and flexibility, as well as spatial specificity in order to accommodate both those who look to be “alone in public” and a multifaceted range of planned and unpredictable events—all this organized and governed in ways that can rely on the distributed control and maintenance by users.

At present, there might be few examples of scaling up the domestic commons, but seeds for incremental urban change exist. In San Francisco, a group of intentional communities in the same neighborhood have built close relationships in which less frequently used resources like tools, kayaks, and larger vehicles are shared. Amenities like yoga rooms and other gathering spaces are opened up to others within this Haight Street Commons.

This group of intentional communities is now working to leverage the city’s Cultural District program to create a Commons District, a neighborhood in which participating residents open up spaces to the larger community in exchange for access to a network of distributed “commons” of the same kind. Across all scales of sharing, negotiation and direct engagement in stewardship is critical for commoning to exist—building relationships with others, forming community that lasts, and evolving a more “shared” city in the process.

Main image: ”House of Commons" Research Exhibition by Neeraj Bhatia and Antje Steinmuller, 500 Capp St Foundation, San Francisco, 2022. Photo © Antje Steinmuller